Salisbury Hall

Curator Alistair Hodgson’s enthusiasm shone through his entire talk about Salisbury Hall and its de Havilland connection. He began with a brief history of the building, a moated manor house dating back to 1507. It has been knocked down and rebuilt several times but retains much of its original appearance. Famous residents include Nell Gwyn in the 17th century and Lady Randolph Churchill who lived there from 1905. Her son Winston Churchill would visit to write his speeches undisturbed. In 1930 the peace and quiet appealed to keen ornithologist and railway engineer Nigel Gresley. He designed some of his record breaking engines under it’s roof. The A4 Pacific Class were all named after ducks and Alistair showed slides of some of them. He awarded a Creme Egg to the first person to identify the Mallard.

De Havilland at Salisbury Hall

1938 saw Geoffrey de Havilland buy Salisbury Hall to expand his aviation business. One of three brothers he grew up on a farm where they built motor cycles in a barn. When he found out about flying machines he was determined to build one. With a loan from his grandfather and the help of mechanic Frank Hearle he rented a workshop in Fulham and built his first aeroplane in 1909. It flew successfully but money had run out. The pair got jobs at Farnborough where Geoffrey excelled in design. In 1914 Geoffrey joined Airco to design, and supervise the construction of and test fly their aeroplanes.

By 1920 he had set up the de Havilland Aircraft Company at Stag Lane, near Edgware designing and selling small aeroplanes. Skilled designer of engines Frank Halford joined Geoffrey to create a series of aircraft called after moths, as he was a keen entomologist.

Aerial view of Salisbury Hall and the Museum

By the early 1930s Stag Lane was bursting and Geoffrey bought land at Hatfield. They expanded their range and made the DH88 comet which won the McRobertson air race to Australia in 1934. It was constructed from a sandwich of plywood/balsa/plywood to keep the weight down. A similar structure was used for the DH91 Albatross a low wing, four engined airliner.

Mosquito – Prototype 1

The Air Ministry wanted a light bomber but would not consider a wooden aircraft. Geoffrey had faith in the design of the DH98 Mosquito and built it in secret at Salisbury Hall. He eventually received orders for fifty and got the furniture industry including G-Plan and Waring and Gillow to manufacture the airframes. De Havilland’s did the final assembly at Leavesden with the co-operation of Handley Page of Radlett. The DH100 Vampire and DH103 Hornet were begun at Leavesden but after the second world war de Havilland’s withdrew to Hatfield.

Salisbury Hall gradually became derelict. although the silk farm in the grounds still operated and made the material for the queen’s wedding dress*. The prototype of the Mosquito should have been destroyed but the works manager dismantled it and hid the parts at Hatfield. The mansion was in a very bad state when Walter Goldsmith bought it from the government in 1955 with the proviso that he should open it to the public. He found sketches of the prototype Mosquito on the walls during renovations and kept them as a visitor attraction. The prototype’s parts were reassembled to its 1943 appearance in 1959, and the following year the first aviation museum in the world was opened with the encouragement of Harpenden’s own John Cunningham.

The Museum

The museum has been completely refurbished in recent years. The DH82 Tiger Moth, a biplane, was used as a trainer by the Royal Air Force and many still fly today. They were used as dive bombers and pilots threw bricks out for target practise. DH82 could be flown remotely by using old fashioned telephone dials which young visitors do not even recognise. The plane’s nickname was the ‘queen bee’ which gave the name to the drones that are buzzing around today.

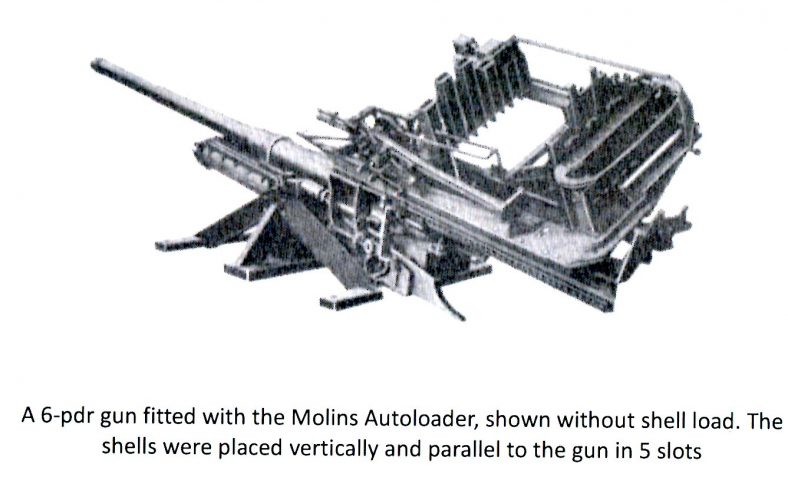

The Mosquito had a crew of two. It could carry a bomb load of up to four thousand pounds. A fighter version mounted 20mm cannon and 0.303” machine guns in the nose. A version carrying a six-pounder anti-tank gun proved most useful in sinking surfaced German U-boats in the Bay of Biscay as they returned to their bases in France. The gun was fitted with an automatic loading mechanism developed from cigarette handling machinery made by the Molins Machine Company.

Many restoration projects are on show. Close inspection shows the finished Mosquito wing to be basically a single structure with the fuselage and wing held together with just four bolts. The Comet I, the first purpose built airliner, which suffered several crashes until the metal fatigue problem was sorted out is being restored with one side as designed and the other holding a display of its history.

The DH89 Dragon Rapide has been undergoing restoration for the last twenty-two years. Alistair himself has worked on a DH112 Sea Venom for the last twelve years. It was a complete wreck when he first saw it but with a special interest in seaplanes he took it to his heart. Plans for a new hangar are awaiting the outcome of a decision by the Heritage Lottery Fund** It also aims to become an education centre for future generations.

Alistair is now the museum’s curator and if his enthusiasm is any guide the plans will come to fruition. He enthralled the audience many of whom are looking forward to visiting the museum. We all send him our thanks for a most enjoyable evening.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Havilland_Aircraft_Museum#Salisbury_Hall

* Editor’s note: A few online sources claim that a silk farm that provided material for the present Queen’s wedding dress was located in Nell Gwynne’s Cottage at Salisbury Hall. No other corroborating sources have been found for this claim.

**

The museum website confirms that the grant has been awarded:

“Thanks to money raised by National Lottery players, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) has awarded a grant of nearly £2 million to the “de Havilland Aircraft Museum in the 21st Century Project.”

https://www.dehavillandmuseum.co.uk

Postscript

When we advertised this talk on Facebook, Vivian Summers posted a photo of the watch presented to his father-in-law for his 20 years of service to the de Havilland company:

Commemorative watch given to Bert Gear on his retirement

“My wife’s father, Bert Gear, actually worked at Salisbury Hall during the war, followed by working at de Havilland in the experimental department, building full scale aircraft in wood, being a cabinet maker by trade. I am fortunate to hold his 20 years service gold watch, when he started in 1941, retiring in 1973. His employment at Hatfield finished in the technical drawing department. His family are very proud of his contribution to the war effort, and beyond, despite the fact that Governments have not recognised the achievements of all these men in producing aircraft.”

Comments about this page

My father, Peter Brett, joined De Havilland as chief propeller designer in 1951, and I imagine would have worked alongside your father. He always said that it was the happiest time in his working life. There was “tremendous esprit de cours within the firm”, and he felt privileged to be there working with “a youngish collection of very competent, very nice, and more or less eccentric people”. He used to say that propeller science was regarded as a ‘black art’ and attracted the sort of people that were great fun to work with.

This presentation was very interesting and very sorry that my wife and I were unable to be there. We hope to go to Salisbury Hall during the Summer and may be able to attend one of your evenings. Thank you so much for including the postscript about Bert Gear. He would have been so proud of the recognition of his work, although he wouldn’t have posted it himself, being a very reserved character, as many of his workmates were.

Add a comment about this page