The Straw Hat and Education

from the Parish Magazine August 1960

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries pressure was brought to bear upon the clergy to undertake the education of children in their parishes. The South Midlands, including Hertfordshire, was regarded as especially backward in this matter. It is rather startling to note how large a proportion of persons in Harpenden in the eighteenth century could not sign their name.

In 1742, besides the churchwardens, nine persons were present at the Easter Vestry meeting. These would be persons of intelligence and parishioners interested in the management of church affairs. Four of the nine were not able to sign their names and placed a cross instead of their signature.

Dickens at Rothamsted

When in 1859 Charles Dickens visited Rothamsted he observed: “Very few (members of the farm workers’ club) could write their names; all who could not pleaded that they could not, more or less sorrowfully, and always with a shake of the head, and in a lower voice than their usual speaking voice. Crosses could be made standing; signatures must be sat down to. There was no exception to this rule.” (“Charles Dickens visits Rothamsted” Records of the Rothamsted Staff Harpenden 1931 p12). Where a home industry like straw plait or lace making turned child labour into profit education had naturally suffered.

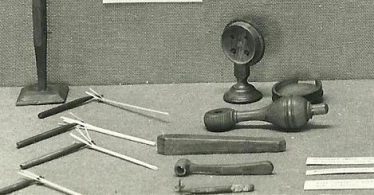

In 1717 the village of Harpenden is mentioned in a petition to Parliament as a place where straw plait was made and in 1725 Defoe in his Tour through England and Wales notes that the manufacture of straw hats “spreads itself from Hertfordshire into this county” (Bedfordshire). Later, during the Napoleonic War the supply of fine straw plait from Italy was cut off, but changes in the technique of plaiting by the use of a patent straw splitter, a plait more comparable to the Italian product, increased the work at home.

Plait Schools – work as you learn (a little)

Since straw plaiting had become a profitable occupation for children, Plait Schools were opened in many villages in the South Midlands and East Anglia. Around St Albans, Redbourn, Harpenden and Luton, straw of a suitable quality was grown and farmers were anxious to supply it in a condition ready to plait as an addition to the profits of the harvest.

Likewise, parents readily sent their offsprings to Plait Schools, where for the payment of twopence a week boys and girls did straw plait. Their mothers taught them to plait before they went to the school and the women who kept the school merely supervised the work. This suited the domestic economy because, while the children were engaged at the Plait School, mother could continue sewing hats at home.All this added to the much needed weekly income. The Overseers of the Poor encouraged these activities, so that the Poor Rate might be kept low.

To justify the term school, “reading” was superficially taught at the Plait School for a short period each day. Occasionally someone interested in children volunteered to read to them whilst they plaited. The clergy were also encouraged to interest themselves in these schools because an opportunity might occur to become better acquainted with the children who regularly attended.

Harpenden’s plait schools

There were many plait schools in Harpenden. In Bowling Alley there was one for girls only. “It was a little low thatched affair” wrote Mr Edwin Grey, “the front door opening direct from the lane into the front room: this same room also served for a schoolroom. One had to take a step down into the room, the said step being inside so that one had to take care when entering the house or one might miss the step and fall head first in.” (Cottage life in a Hertfordshire Village.)

At Kinsbourne Green Mrs Farr had another Plait School, but perhaps the best known school was kept by Betsy Crane, situated in Straker’s Lane, now Station Road near the present Post Office. Of this Plait School, Mr Edwin Grey wrote: “I had to stand by Betsy’s knee whilst, with her assistance, I spelt letter by letter one or two easy words from a big book; of the plaiting lesson I remember nothing… The first thing to be done was Testament reading, each scholar reading or floundering through a verse and then handing on the book to the next boy or girl.”

The exact site of Mrs Bruton’s establishment is difficult to find. From Miss Vaughan’s valuable pamphlet on Harpenden it appears that the school faced east in the low cottages which form a continuation of Leyton Road. On the other hand, some informants believe that Mrs Bruton’s school was held in the building on the east side of the churchyard where there is now a shop and on the south wall of the gable end the date 1779 is picked out in black-headed bricks. Here Mrs Bruton conducted the school and for about a quarter of an hour each day she taught the children to read the Bible. But these lessons were entirely superficial.

From forty to sixty children were accommodated in this school and if it resembled the other establishments it was heated by “dicky pots”, that is tins or earthenware jars filled with hot charcoal. These schools were usually held from 9am to noon and from 2pm until 5pm and some schools opened again from 6pm until 9pm.

Conflicting evidence prevents any exact estimate of the earnings of those who attended the schools. A child of eight years might earn ninepence a week, while a child of thirteen could earn two shillings a week. Girls were the chief workers because a boy was more usefully employed on a farm where the work was less exacting.

Beside these Plaiting Schools work rooms or sewing rooms provided employment for women who sewed the straw plait into hats. Messrs Vyse and Co of Luton owned a workroom in Southdown.

The Workshops Regulation Act

The Workshops Regulation Act of 1867 was designed to put an end to these schools, but the Act was not successful because the definition of Plait School was not made with sufficient precision. It was only the philanthropists who definitely desired to terminate these schools. The farmer, the manufacturer, the overseer, the parent and the schoolmistress had a vested interest in the school.

The farmer profited considerably by selling straw as the grain was left intact. The farmers of Harpenden, Redbourn and neighbourhood reserved fields of suitable corn to sell to the straw plait dealer. When the corn was carefully reaped the buyers came and selected the straw, cutting off the ears of grain which were left behind. The straw was then cut into the required lengths and sold and distributed by various means to the plaiters. After the plait was made in the homes or schools it was sometimes taken to St Albans market on Saturday mornings, in other cases the dealers came to the house of the plaiter. Further bunches of lengths of cut straw were left at the house. Those plaiters in need of ready money went to a local shopkeeper, who was also a plait dealer.

By means of the plait trade the district became prosperous. But the general effect on the children and young people was not commended.

During the the nineteenth century the Hertfordshire Diocesan Board of Education passed resolutions intended to help the clergy in dealing with the question of Plait Schools. It was suggested that plaiting might be allowed more often in the parish schools. If that was not possible auxiliary schools might be opened intended for making plait where other subjects might be taught. In any case clergy were urged to interest themselves in the Plait Schools.

Comments about this page

During her visit in 1821 to friends at Blakesleys (now Harpenden Hall) where Mr Phillips ran the Dissenting Grammar School for Boys, 18 year-old Elizabeth Read and her sister visited a cottage to see straw plait made. In her journal for 8 October she wrote:

“A neat, pretty woman of the name of Smith and her little girl and a neighbour were all busy at work round the fire. It is astonishing to see the rapidity with which little children do what appears at first sight so complicated. Some do as much as 32 yards every day, but this is not very common. The good woman shewed us the whole process of her little manufacture. The stalks of wheat only are used (or are the best) and only the middle of each stalk. Different sized instruments are used in splitting it according to the thickness of the straw and the quality of the plait to be made, but before splitting the straw it is bleached by the steam of brimstone, and after it is split it is put in a rolling machinge to render it more pliable. This is of wood about the size of a coffee-mill and fastened against the cottage wall. We were then taught the plait and each did a little and I believe the woman thought us very good scholars. The other woman was doing it with double straw which is in imitation of Dunstable straw: the kind we learnt is called Devonshire plait and is the commonest sort. It is necessary to keep the straw damp or it breaks easily. … Thus the days go on and how little is done! To be sure I have learnt to plait – but whether it will ever be of any use to me I cannot tell. I should never plait straw for my living if I were ever so much reduced, for I could not do it so fast as any little girl about here and a family is but maintained when all the members are employed at this work from morning to night.”

The Read family lived at Wincobank Hall near Sheffield. From A Visit to Harpenden: Extracts from Elizabeth Read’s Journal, 1821. (LHS archives: BF 20.8(b).)

Add a comment about this page