This memoir was submitted to the Society’s competition – “I remember … Recollections of Harpenden and Wheathampstead before 1914” in 1979. It was published in Newsletter 114, September 2011.

My father had worked as a grocer’s assistant in the shop of Mr. C J Austin, High Street, Hemel Hempstead. He married my mother in the Wesleyan Church in this town. When he married he was appointed a branch manager of the shop at Harpenden owned by Mr. Austin. This was situated on the west side of the green in the area known as the Bowling Alley. The postal address was Wheathampstead Road, later to be named Southdown Road. It was at the lower end of Walkers Road. The building was a three-storey one almost opposite the Rose and Crown public house. I do not know the date of the building but I would like to think it was between 1900 and 1902.

Detail of postcard of Southdown, showing the shop and home – now 102 Southdown Road. Credit: LHS archives – LHS 279

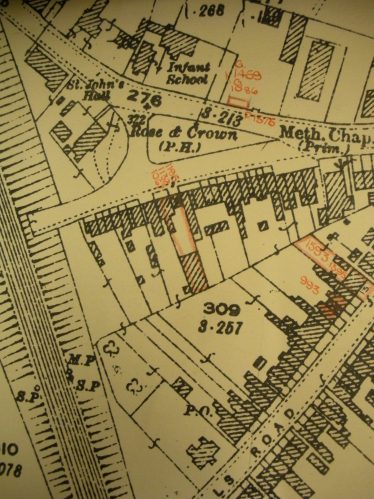

Extract from 1898 OS map. The post office was at the top of the terrace, so the white cloth could be seen across the gardens. Credit: LHS archives

Within my memory an assistant lived with us. Up to 1914 he was Hubert Wren, a son of the wheelwright at Wheathampstead. He had booked a passage to New Zealand (see comment below), and was allowed to emigrate there in August in the first weeks of the 1914-1918 war. His brother Cyril carried on his father’s business in Wheathampstead.

A white cloth to announce my birth

I was born in March 1903 and appeared a month earlier than expected. The midwife, Nurse Oggelsby, was booked but was engaged on another birth and could not come. Someone else was free and looked after my mother though my father was not satisfied with her services. When my appearance was imminent my parents had arranged to display a white cloth out of the rear window of the top storey of the house so that Mrs. Humphrey, the postmistress for the Bowling Alley, could see the cloth and come along and help with the proceedings. The Post Office was in Cravells Road about three houses down the road from the Midland Railway Bridge.

Their garden was a long one and a gateway led into Walkers Road and Mrs. Humphrey could take a short cut from her house to ours. My Post Office savings book until recently was numbered Bowling Alley 386A. I still keep the book.

My parents were great friends of the Humphreys. Mr. Humphrey was a tailor and I remember him sitting cross-legged on his bench to do his hand sewing; he kept bees in his garden but he died many years before his wife, who lived to a great age.

Next door to our shop was Mr. Fred Oggelsby’s blacksmiths and wheelwrights shop. My brother and I could look over the garden wall and see the iron tyres being heated, fitted on to the wooden felloes of the wheel and then cooled to shrink the tyre. We could also watch the making of horse shoes and the shoeing of the horses. In 1914 they made stocks of horseshoes for the Government; they also shod the horses for the army contingents billeted in the village. Mules used by the army were particularly difficult to shoe; the animal would be taken down to the green in front of the houses, a lasso would be thrown round each leg and the mule thrown to the ground and a man would hold each rope. The shoe would be heated at the forge, each leg in turn would have the old shoe removed and the new one fitted. It took about six men to complete the operation.

Living behind and above the shop

Our house had a living room on the ground floor behind the shop and outside was a stable for the pony used for deliveries. There was also a store room which contained a machine with revolving brushes used to clean dried currants. Paraffin oil was stored nearby in a barrel and there was a large outside toilet. Over the shop was a large sitting room, behind this a small room and an indoor toilet. Three bedrooms on the top floor were used by ourselves and the assistant. A large cellar under the shop was used to store butter and other provisions. Large blocks of salt about 2 feet long and 9 inches square were sawn up into 2 inch blocks in the cellar. The two lower floors were lit by gas and incandescent mantles. The cellar had a small fishtail burner; the gas burned without a mixture of air and gave a feeble light. In the sitting room over the shop where we spent Sunday evenings there was a fitting like an inverted “T”. The tube of this contained water to prevent the gas from leaking. When it evaporated it had to be filled with water, probably in the middle of Sunday teatime. We went to bed on the top floor by candlelight. Hubert Wren was a Wesleyan local preacher and he used to write his sermons by this light in his bedroom but he came down by the fire in cold weather.

School days

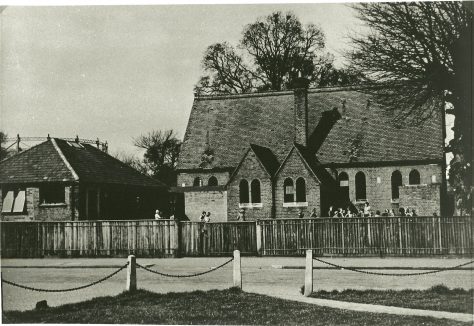

I first went to school about the age of five, to the St. John’s Infant School which was only across the green, a triangle in front of the house. Two teachers I remember were Mrs. Bowden and Miss or Mrs. Kate Abbott. There may have been another teacher named Miss Wilmot. I still have a photograph of the class with Miss Abbott. When I was seven I went to the Harpenden Board School near the station. There was a National School near the church controlled by the church authorities; the Board School was governed by the School Board and was non-sectarian. This school was about a mile from home and we walked each way twice a day. School meals were not provided but scholars could take sandwiches. My mother preferred us to go home for the mid-day meal when there was a two-hour break.

St John’s school, on the Green, opposite the house where Frank grew up. Credit: LHS archives

The holidays were a fortnight at Christmas and Easter, a week at Whitsun and five weeks at August. On Empire Day, May 24th, we all wore red, white and blue buttonholes and had special talks on the British Empire. We sang national songs – “Rule Britannia”, “The Maple Leaf” for Canada and others, ending with “God save the King” and then had a half-day holiday. On the day of King George the Fifth’s coronation we had sports on the Common and a tea near the Public Hall; we were each given a mug with the King and Queen’s portrait on the side and a rose. In the evening the Common was lit up with fairy lights suspended from the trees. These were small coloured glass jars with short candles inside. There was also a display of fireworks which we saw on our way home.

Gang warfare!

Boys organised special pressure groups on occasions at school. On Oak Apple Day to commemorate the hiding of King Charles II in the oak tree all boys who remembered wore an oak apple. Gangs armed with stinging nettles held in a handkerchief would go round and any boy without an oak apple would be stung on the bare legs. We wore shorts and stockings turned down below the knee, that is for the smaller boys, older ones wore breeches buttoned below the knee. On boat race day it wasn’t safe to proclaim one’s colours, light or dark blue, unless you were with a crowd of similar supporters. A lone supporter was liable to be beaten over the head with the caps of the gang of the opposing side. When there was snow on the ground there was a battle between the National and Board School boys.

A penny a truck load

Spare time occupations were varied. In the autumn we picked blackberries on the Common or hedgerows and after the harvest gleaned corn in the fields, which was used to feed the hens which nearly everyone kept in the back garden. Most boys had a box on wheels to collect horse manure from the roads for use on their fathers’ allotments. They generally had a penny a truck load for their efforts; we had a pony so there was no need for us to collect horse manure but we did occasionally collect sheep manure from the Common where the sheep grazed to make liquid fertiliser.

Wintertime games

There was only rather slow moving horse-drawn traffic on the roads and in winter we played with whip and top or bowling hoops along the roads. The tops were of three grades, a short fat one called a Joey, a medium one which girls used shaped like a carrot and known by that name, and a racer shaped like a mushroom which could be sent quite a distance with each strike of the whip. Boys bowled iron hoops propelled with an iron loop which circled the rim of the hoop while the girls used wooden hoops propelled with a stick. One activity that boys liked doing was to hang on to the rear of the cart or trolley without the driver’s consent. One’s friends or enemies would shout “whip behind, mister” to draw attention to the unwanted passengers.

Home – and hospital – remedies

While living in Harpenden I contracted scarlet fever and was taken to the isolation hospital at St. Albans. The matron fetched me in a horse cab in the hot summer of 1911 and I stayed there six weeks. Diphtheria patients were sent to another hospital nearby. This disease often proved fatal if early treatment was not available. Home remedies were used for minor ailments – for a cold camphorated oil rubbed on the chest or goose grease smeared on brown paper and hung next to the skin over the chest were considered good cures. The brown paper was stiff and uncomfortable. A cold key dropped down the back was said to cure nosebleeds. A small onion warmed in the oven and placed in the ear was good for ear ache. A warm sock tied round the throat at night would cure a sore throat. Oil of cloves painted on the gums would ease the toothache. Children were given Spring medicine made of brimstone and treacle early in the year.

To school by train

A number of boys and girls from nearby villages were sent to Luton Modern School but those from Hertfordshire were not eligible for free places. Some passed a scholarship for St. Albans Grammar School but Harpenden boys paid a fee each term for the Luton School. I think it was two pounds per term. We travelled by train to Luton and I remember the carriage being lit by gas. To light them a man had to turn on the gas at the end of the coach, climb onto the roof and lift a lid above each compartment and light the gas below. In winter, foot warmers, large metal containers about two feet long were filled with hot water and placed in the compartments. We were always interested in the branch line train which ran from Harpenden to Hemel Hempstead and Boxmoor. This was a short train with hard wooden seats for the carriages. The engine was not changed for the reverse trip but the driver changed ends and signalled to the fireman at the rear for more or less speed. The line had steep gradients and the train was known as the Knickerbocker or Knicky.

Packing & delivering the groceries

There were very few goods pre-wrapped and most of them had to be cut and weighed in the shop. Sugar came in two-hundredweight sacks, bacon in the complete side of the pig, cheese in a circular block about eighteen inches in diameter and the same in height. Cheese was cut with a wire fastened to two pegs and pulled through the cheese. Butter and lard were delivered in half-hundredweight boxes and cut as required. I remember eggs being sold at twenty-four for a shilling at Easter when they were plentiful. Boiled sweets were four ounces for a penny. Players and Gold Flake cigarettes were threepence for ten and Wild Woodbines five for a penny. There was a popular song about a boy who bought a penny packet of cigarettes which made him ill – the song recorded that “after five little whiffs, in five little jiffs, he was lying on the tramway lines”.

The pony and cart was used for deliveries to customers and the assistant made the deliveries. One day to Batford, another day to East Common and Childwickbury, another to Wheathampstead. Orders would be collected in the mornings by the assistant travelling on a bicycle and deliveries in the afternoon of the next day. A boy came in on Saturdays and made local deliveries. The pony was kept in the stable behind the house and the cart in a shed on Father’s allotment. In the summer the pony was put in a field behind the Plough public house for grazing. He was sometimes difficult to catch, even with a handful of oats, when required for deliveries.

Being in a shop we had to deal with all the tradesmen who dealt with us. At one time we had four milkmen calling – Mr. Titmus of St. John’s Road, Mr. Wilkinson of Aldwickbury Farm, Mr. Dickinson of Cross Farm and another so mother had to have half a pint from each. Milk was delivered in a float whose floor was about eighteen inches from the ground. There was a broad ledge in front over the axle on which stood a churn with a capacity of about twenty gallons. The milkman would shout to his pony and jump on the float as it moved off. He would carry the milk to the customer in an oval can with a lid and holding about two gallons. He would ladle out the quantity required into the customer’s jug. We had two bakers call, Mr. Turner and Mr. Irons, both in Cravells Road. The latter was known as the midnight baker and Mr. Titmus the midnight milkman because of their late evening deliveries.

Wesleyans

My parents attended church or chapel whenever possible. My brother and I went with them as we grew older. There was a Primitive Methodist church about a hundred yards from home but they walked to the Wesleyan church in Leyton Road. I think it would be because my mother belonged to this denomination before she married. Mr. and Mrs. Humphrey were also Wesleyans. My mother took a class in Sunday school at one time. I remember various persons who taught in Sunday school – Mr. Henry Salisbury, his son Edgar and daughter Susan, Mrs. Frank O. Salisbury, Miss Margaret Gregory, Miss Mosscrop, Mrs. Norman and others. After an illness I was shy at attending and played truant until this was discovered. I was then escorted by two young ladies, the Misses Edwards from Cravells Road.

The Wesleyan Chapel, Leyton Road, c.1900

Local personalities

A few other personalities might now be mentioned. Four houses from us was another grocer’s shop run by Mr. George Grey. I travelled to school with his son Walter. We were friendly with Will and Jack Hysom whose father was landlord of the Rose and Crown. Before 1914 horse races were run on the Common and extra police were drafted in. Will and Jack attempted to enter their house but were stopped by the police who were having lunch there. They had to stay outside until they caught their mother’s eye. Mr. Dench was landlord of the Plough and our pony grazed his field in summer. Mr. Chalkley cut our hair for twopence each. I believe the charge for adults was more. He used his allotment as a small nursery for annual flower plants, brassicas, leeks etc. Harry Pearce the butcher used his allotment as a slaughter house. I think he went bankrupt. About four houses up towards the railway bridge lived Mr. and Mrs. Carter. A relation at Batford went bankrupt and I remember being told that one of the creditors shouted in her letter box “pay your debts Dorcas Jane”.

David Ward was a carpenter and joiner who lived near the lower end of Cravells Road. He was also a part-time fireman. I worked with him after 1918. Will Freeman was also a tradesman in the building trade. He made moulds for blocking straw hats for the factory next to his premises in Grove Road. I bought some of his tools. Mr. and Mrs. Gregory from Station Road were also friends of my parents. In the period of this essay the 1914-1918 war started. Men of the Nottinghamshire and Derby Regiment were billeted in the village. We had the orderly NCO’s in our house. Tom Putterill was the leader of the Salvation Army. The members met under the Baalamb Trees and for the collection pennies were thrown on to the drum. Tom would count the proceeds and if not up to standard would ask for another throw.

Editor’s notes:

This was one of many responses to the Society’s 1979 request for pre-1914 memories.

Many of the people named are listed in the Directories of the period held at Harpenden Library. The Richardsons do not appear at all as they lived on the premises, which were listed as Austin & Co, Grocers.

The Harpenden and Wheathampstead local history series of booklets include references to the following;

Thomas Wren, wheelwright and active Wesleyan, p134. George Grey, Grocer, p189. John Irons, Baker, p202. Herman and Harriet Humphrey, p204. 1910 Empire Day celebrations, p269.

The 5th (Territorial) Battalion of the Nottinghamshire & Derbyshire Regiment (the Sherwood Foresters) was mobilised immediately after war was declared and moved to Harpenden. It was moved to Braintree in November and was part of the first Territorial Division to land in France in February 1915.

Comments about this page

I was recently sent a copy of this article, by my mother’s English cousin, as it mentions my grandfather Hubert Wren, the grocer’s assistant and Methodist local preacher. He travelled to Australia in 1914, not New Zealand, and had to wait 6 years for his fiance to join him. Very interesting to read about the history of the time.

Ed. note: we had been alerted to this mistake by Amy Coburn. Thank you for contacting us about it.

Add a comment about this page