A Passion for Plants

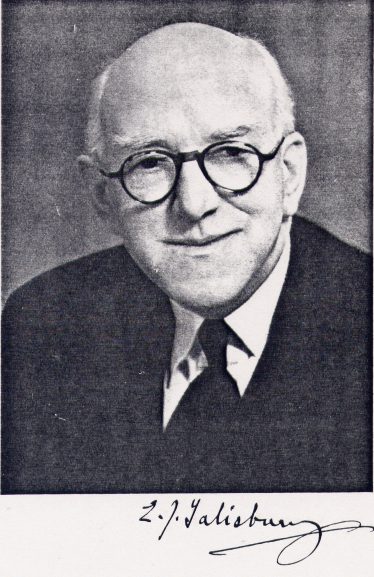

Sir Edward Salisbury, botanist, 1886-1978

This article first appeared in Hertfordshire Countryside in 2006.

Sir Edward James Salisbury

Almost 120 years ago Harpenden became the birthplace of one of the leading British botanists of the twentieth century. Sir Edward Salisbury was not simply an expert on plants themselves. Inspired by the countryside of his native Hertfordshire, he was one of the first to study them in relation to their natural surroundings.

Born at Limbrick Hall on Harpenden Common on 16 April 1886, Edward was the youngest of nine children of businessman James Wright Salisbury and his wife Elizabeth. His passion for plants began at an early age. During family outings into the surrounding countryside, the youngster would collect flowers to grow on his own patch in the garden at home. He attached a label to each one giving its Latin name, and his brothers duly dubbed the plot ‘The Graveyard’.

Limbrick Hall in 1929, from the Auction brochure, showing part of the 2-acre gardens bordering Harpenden Common – LHS archives LAF 12

After attending a boys’ preparatory school in St Albans, Edward was sent to University College School in London. But he still found time to go plant-hunting around Harpenden on his bicycle during the holidays. He improved his knowledge through regular visits to Rothamsted Agricultural Research Station, across the Common. By the age of sixteen, he knew exactly what he wanted to do even if it meant being ragged at school. On one memorable occasion, a teacher asked each boy in the class his future plans. When the Harpenden lad announced he was going to study flowers and plants, there was such an uproar the lesson had to be abandoned.

Edward Salisbury went on to study botany at University College, and on graduation became a research student. Before long, he was helping to lay the foundations of a brand-new branch of botany called plant ecology. Instead of studying plants in isolation, scientists began investigating their relationship with their environment. The young man carried out some of his earliest fieldwork on Harpenden Common, where he demonstrated the importance of soil moisture in determining the distribution of bracken.

Founder member of the British Ecological Society

When the British Ecological Society was founded in 1913, Salisbury became a founder member. By now he was working on an even greater project involving the oak-hornbeam woodlands of Hertfordshire. The botanist recorded the light intensity in woods at different seasons of the year, and studied its effect on the flora beneath the trees. This classic study was the first if its kind in the country. When his research was published in 1916 it revolutionised the understanding of woodland ecology.

Salisbury ’s work reached an even wider audience when he began writing textbooks with fellow botanist F E Fritsch. The first to appear was An Introduction to the Study of Plants in 1914, and the last in the series was Plant Form and Function (1938). Aimed at secondary school pupils and first year university students, the famous Fritsch & Salisbury titles were among the most successful botanical textbooks ever published. Both well illustrated and eminently readable, they inspired countless budding biologists.

By 1929, the Harpenden man was Professor of Botany at University College. He was also busy with more pioneering research, this time on the seed output of plants. Over a twenty-five year period, he counted and weighed the seeds of around half a million individual plants, from more than 249 different species. He published the results in 1942 in The Reproductive Capabilities of Plants, the first work of its kind on the subject. A major contribution to botany, his work provided hard evidence of the effect of habitat on seed production.

A love of gardening

Salisbury ’s most successful book, however, was about gardening, a subject which had fascinated him from childhood. Following his marriage in 1917, the botanist and his wife Mabel had settled in Radlett where they built a house called ‘Willow Pool’. At their new home, he created a showpiece garden which soon became well-known because of the remarkable variety of plants which he successfully grew there.

When his book The Living Garden appeared in 1935 it proved an instant hit with the public. Subtitled The how and why of garden life, it successfully combined a practical gardening book with the science behind it all. Just as he had done with this textbooks, Salisbury revealed a striking ability to simplify his subject and present it in an interesting way. Indeed, members of the Royal Horticultural Society were so impressed with the work that they awarded the botanist their Veitch Memorial Gold Medal.

Kew Gardens in wartime

When the post of director of Kew Gardens fell vacant during the Second World War, Salisbury was the natural choice for the job. He faced a difficult task. The library and herbarium had been moved out of London for safekeeping, and the staff were depleted. Bombs were a constant threat. Just months after he took up the post in September 1943, a bomb landed next to the Temperate House, damaging neighbouring plant houses in the process.

The end of hostilities brought fresh problems for the botanist. With little funding available, he faced an uphill struggles trying to implement the post-war restoration of Kew. His most successful enterprises involved the plant houses. Salisbury not only initiated the restoration of the one hundred year old Palm House. Following a trip to Australia in 1949 as leader of the British delegation to the Commonwealth Agricultural Conference, he organised the building of the Australian House for plants from the antipodes.

Knighted in 1946, Sir Edward retired from Kew ten years later. As his wife had been suffering poor health for some time, the couple moved to Bognor Regis for the beneficial sea air. Sadly she died soon afterwards. Nevertheless, the widowed botanist remained a resident of the West Sussex resort, where he continued his research into fruit and seed pollination. Indeed, he turned out articles and papers right up to the year of his death.

Sir Edward Salisbury was ninety-two when he died on 10 November 1978. He had devoted his entire life to botany. Yet he was not only, as The New Scientist once put it, ‘a lifelong lover of things that grow in the earth’. The man from Harpenden was also a trail-blazer in the study of plant ecology.

An Obituary published in The Times, 14 November 1978, gives more information about his scientific work and publications. It is attached below.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page