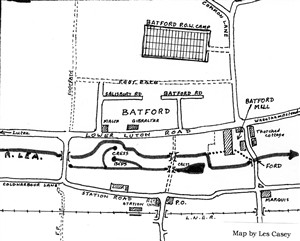

Sketch plan, showing location of the camp. Credit: Les Casey

In 1942, after the British successes in North Africa, there were thousands of Italian prisoners, and camps were needed to house them. In January 1943 the War Office compiled a list of possible sites in Britain, (the threat of invasion had passed,) and at the beginning of February told the Harpenden Urban District Council that they intended to requisition a site at Batford to the north of Common Lane, and commence immediately to build a Prisoner of War camp.

The Council raised no objection, asking only that it should not encroach on to the Council’s allotment site, and that it should remain only for the duration of the war. There were not many houses in Batford at that time, and the Council pointed out that the sewage system would need enlarging. The camp opened before the system was ready, and toilet arrangements for the first few weeks were rather primitive.

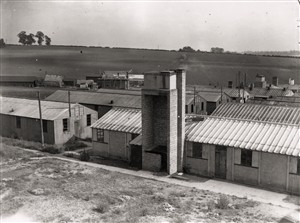

The vacated camp Sept 1948. Credit: LHS archives

The vacated camp Sept 1948. Credit: LHS archives

Italian prisoners

No. 95 P.O.W. Camp, Batford, opened in May 1943 for Italian prisoners, originally housed in tents which were gradually replaced by huts. It accommodated about 600 men. In October 1943 the Italian government signed a peace treaty with the Allies, and shortly afterwards declared war on Germany. This altered the status of the Italians. Although still prisoners, they would be granted certain privileges and better treatment. In July 1944 the camp was re-designated as an Italian Labour Battalion Camp. The men were employed mainly on local farms. In November 1944 the Italians were moved out: some into hostels, and some were lodged at the farms where they were working.

A German P.O.W. Working Camp

Picking up potatoes near Harpenden. Credit: LHS archives

The camp then became a German P.O.W. Working Camp, with 750 prisoners. They were “other ranks” (ie not officers) and as such, under the terms of the Geneva Convention, they could be required to work for their captors. Some were set to do general labouring, but most, in these early days, were employed in agriculture. The men were taken each day, in small working parties, by lorry to the farms where they were to work.

Lectures and film shows

The prisoners were restricted to camp in the evenings and at weekends, but they had many ways of spending their time. They had a film show once a week, and there were occasional lectures organised by the British, and discussion groups organised by the Germans themselves. The prisoners had their own officials: there was a Camp Leader, a Political leader, and a Study Leader. The discussion groups took place regularly: they were well attended and aroused much interest. They covered a variety of subjects, such as politics, current events, trade unionism and so on. Many of the talks introducing the discussions were given by the prisoners themselves. They had their own drama group, who put on the occasional show for their fellows. The camp had a library, with a selection of both German and English books. There was a camp newspaper, in German, and a selection of British newspapers. There were classes to learn English, French, German literature, history, geography, mathematics, chemistry, physics, applied electricity, building and architecture, and commerce. There was a wireless in the Camp Leader’s office, with about a dozen loudspeakers around the camp.

Discipline and football matches

The guard at Batford, presumably post-1946. Credit: LHS archives

But along with all this activity, discipline was maintained. In December 1944 twenty-one prisoners were charged with collective indiscipline. They refused to work because they had only one uniform each. They were given periods of detention up to twenty-eight days, in some cases with punishment diet no. 1 (which was, I think, bread and water). The men played football within the camp, against each other, until the war ended. Then they were eventually allowed to play civilian teams within a five mile radius of the camp. In August 1947 their team played Harpenden United Football Club in Rothamsted Park. The Germans were delighted to be leading 2 – 0 at half time. They were even more delighted at the end of the game, which they won by 5 goals to 2.

After the War

At the end of the war in May 1945 the men hoped to return home. But, for several reasons, they were not immediately repatriated. Germany was in a state of chaos, and with no civilian government, was under military rule. There were severe shortages of food and accommodation, so although Germany could have done with the men’s labour, it was not possible to return them. Besides, until Britain’s own servicemen had been demobbed, the German labour was needed here, particularly in agriculture and rebuilding. Also the British Government wanted to de-Nazify and re-educate the men before their return. So the camps remained.

Satellite hostels: Hatfield Hyde, Stanborough, Lemsford

All Prisoner of War camps were inspected by representatives of the Red Cross, who reported on all aspects of the camp. Unfortunately those of the war years appear not to have survived. At that time Batford Camp had three satellite hostels, one at Hatfield Hyde with 60 men, another at Stanborough with 56, and the largest at Lemsford, which held 265. There were also 932 men in the main camp at Batford. Fifteen months after the war’s end, repatriation was under way, and hundreds of men had gone from Batford, but were replaced by men from other camps.

Group of German Prisoners on 14 June 1946 – Back row from left to right: Theo Nolan, Werner Krieger, Horst Muller, Karl Heine, OHS Schieben, and unidentified. Front row, left to right: AHS Thuringen, Bruno Liebich, AHS Pommion, Horst Lange. Credit: LHS archives

Bruno Liebich

Bruno Liebich spent a year working on farms around the area, at Bovingdon, Berkhamsted, Slip End, Tring, Elstree, and Gorhambury Park, and found it tedious and boring. He was hoeing, potato picking, and laying drainage pipes in the winter. After a year he managed to get a job as a dustman for St Albans Council, together with eleven other POWs. He reckoned that was one of the best jobs in the camp. He was also transferred to the hostel at Lemsford.

Prisoners from Canada and USA

In March and April 1946 there were two large intakes, one from Canada and one from the USA, with a total of 939 men, 200 of whom had gone to Lemsford, the remaining 739 men staying at Batford. Morale amongst these men was not very good. Those from America were particularly disgruntled: they had been told by the Americans they were going straight home to Germany. Instead they landed at Liverpool and were brought to Batford. Before coming to England they had been employed in picking oranges in Florida sunshine. Now they had the dull, cold and wet English climate.

Attitudes towards Nazism

This new contingent was also not happy because half of the men in the main camp were still in tents. The Commandant promised that these would be replaced by huts, and the work was completed by the end of September. Also many of the men, those who lived in Eastern Germany, overrun by the Russians, had had no news from home for a couple of years. But perhaps the main cause of discontent was the uncertainty as to the duration of captivity: they had no idea of how long they were to be held. This large intake completely altered the political balance of the camp. All prisoners were screened, and graded as to their attitude to Hitler and Nazi beliefs. Those who still thought Hitler was right were graded “C”: those opposed to Nazism were graded “A”; and those in a state of uncertainty “B”. influence, were transferred to another camp (not specified, but probably Oldham , which had a reputation for dealing with hard cases.)

Restrictions on prisoners

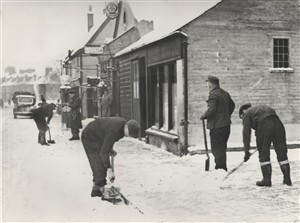

PoWs sweeping snow in Harpenden 1947. Credit: LHS archive copy of photo by Frederick Thurston – his studio is on the background

The war ended in May 1945, but restrictions on the prisoners were not relaxed until the tail end of 1946. They continued to work outside camp on weekdays, but in the evenings and at weekends they were confined to camp. There was little public sympathy for them. Firstly, nearly every family had been affected by the war in some way, and were in no hurry to forgive and forget. Amongst most people these camps aroused feelings of revulsion for all things German, including the prisoners. An anti – fraternization law was passed, making it illegal to talk to the prisoners socially: only conversation in connection with work was allowed. Most of the men were working on farms: some were collecting the potato crop from Harpenden Common: a few became dustmen for the U D C: and some were employed on general labouring, preparing the foundations for Grove Road to be built, amongst other jobs. (In January and February 1947 several men were engaged in snow clearing, for days on end.) But by 1946 the public mood had changed. The anti – fraternization laws were being more or less ignored, and tentative friendships were established. Repatriation started in September 1946.

‘Greet all my friends of the Social Hour’

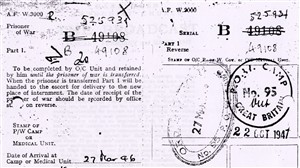

Registration Card (?) with Date Stamp. Credit: LHS archives

Three months later in December prisoners were allowed out of camp at weekends, unescorted. Many of the men sent letters from home: this is just one example. “I will maintain the friendships I made during my imprisonment in England. Pure friendship with dear, warm hearted people. Greet all my friends of the Social Hour, the ladies and gentlemen who gave me so much – tea, coffee, cakes, music, songs and films. Also the dear little children in the Sunday School. I shall never forget these good people in all my life. I think a great deal about the beautiful evenings at the Social Hour. It was always a great pleasure to come.” S. C. The Church also opened its doors at 9.00am on Sunday mornings for the men to attend a Lutheran service, in German, conducted by Pastor Gunter Bartolomans. The Roman Catholics attended Mass at Our Lady of Lourdes in Rothamsted Avenue.

Friendship and marriage

Other people were trying to make life a little better for the prisoners. In February 1947 Arthur Hopkins wrote to the Harpenden Free Press, asking Harpenden people to help lay a firm foundation for peace. He said he had been told that the Germans could be invited out to private homes on Sunday afternoons between 12.30pm and 5.30pm on application to the Commandant, and he invited people to do this. Many people did so, and friendships were formed, in some cases, more than friendship. In March 1949 one young lady, Eileen T., married Rudi W., an ex POW. They had met when her parents invited two men home for tea. Rudi had elected to stay in England, and worked at Aldwickbury nurseries. It was also possible at this time for private individuals to employ the men on a variety of jobs, after applying to the Commandant. Many people asked for them as gardeners.

Christmas celebrations

At Christmas 1947 the prisoners were allowed to travel within a 100 mile radius of the camp, rather than the previous 5 miles. 330 of the men had 48 hour passes to visit friends. Many others were invited out to Christmas dinners and parties. Altogether, 80% of the men were out of camp. For those who were left, large numbers of parcels were received, some from home (in Germany), some from local people. Some of the parcels from Germany contained foodstuff and such titbits as packets of biscuits. There were plenty of Christmas cakes at camp, the POWs having specially saved up their rations. Most of the British troops were on leave; those remaining had their own Christmas dinner.

Returning to Germany

As repatriation approached there were, perhaps surprisingly, a considerable number of men who did not want to return to Germany. Many of them lived in Eastern Germany, which was then controlled by the Russians, and from the little news that they had received, preferred to remain here. Others, possibly, wanted to start a new life. Whatever the reason, nationally, over 250,000 men applied to remain here. They were interviewed to see whether they were suitable. If accepted, in accordance with the Geneva Convention, they were sent to Munsterlager in Germany to be officially discharged from the Forces. Then, as civilians, they were given ration books, money and travel warrants to visit their families. They were allowed to stay for a month before returning to Britain to work. It is not known how many men from Batford did this: certainly quite a few did. But the majority went home.

The end of the camp

Repatriation was completed in July 1948. The Urban District Council then took over the camp, renovated the huts each to accommodate two families, one at each end, and used them to help the housing shortage. The site was closed in 1958, when the Batford housing estate of Milford Hill and Tallents Crescent was built. There were no escapes from Batford Camp, although there was a moment of excitement when foundations were being dug for the housing estate. A large tunnel was found, extending for some distance. At first it was thought that it might be an escape tunnel, but after examination it was found to have been dug many years earlier, to obtain chalk for mixing with the soil, a common agricultural practice in this area.

Thanks to Mr Bruno Liebich, The National Archives, and High Street Methodist Church.

Eric Brandreth June 2006.

Postscript from Eric Brandreth’s files, added in January 2016:

Terry Bentley, of 35 Common Lane, was digging in his garden in October 1963 when he hit something hard: it turned out to be a large buried petrol tank. He reported it, and when it was removed later, it was found to still contain a considerable quantity of petrol. Terry was relieved to see it go. A few days earlier he had been weeding his garden with the aid of a flamethrower!

Batford Methodist Church opened a canteen for forces every night from 7.00 till 10.00 pm. Several of the British soldiers from the camp regularly attended the Church, among them John Ollerenshaw and George Knowles.

October 2014:

We have discovered that there are many interesting Comments on the Herts Memories version of this page, including from Bruno Liebich. See Comment below for the link.

Comments about this page

The hut was the second Harpenden run by Bob Beckwith.

I was a scout there. When it was demolished we had a new hut built in Tallents Crescent which is still there

Alfred Daffurn had been in service long enough at Luton Hoo, so in c.1946 he rented the grounds of Aldwickbury House in Harpenden and built up a thriving gardening business of his own. It was hard work, even utilising a small labour force of ex-German prisoners of war from the Batford camp. Success brought with it paperwork that kept himself and Mary up until the early hours, but he still found time to become a Committee Member of the newly re-formed Harpenden Horticultural Society. Already a highly respected judge at Chelsea, he became a familiar figure adjudicating at local shows, donating a cup for growers of chrysanthemums, his own speciality.

– adapted from Jill Hunt’s article in Hertfordshire Countryside, May 1998, on Alfred Daffurn, who worked at Luton Hoo from 1934 to the end of WWII and then for H E Joel at Childwickbury from 1949 until his retirement in 1972.

Many interesting comments have been added to the Herts Memories page on the Batford PoW camp – see http://www.hertsmemories.org.uk/page/no_95_batford_prisoner_of_war_camp?path=0p34p97p. We would particularly like to hear from Bruno Liebich.

See also our new pages on gifts made by PoWs and treasured by Harpenden children who received them – click on each link for these stories.

Very informative!

In the 1950s the 10th Harpenden Scouts had their scout hut on the Batford site. It was one of the old Camp huts.

Add a comment about this page