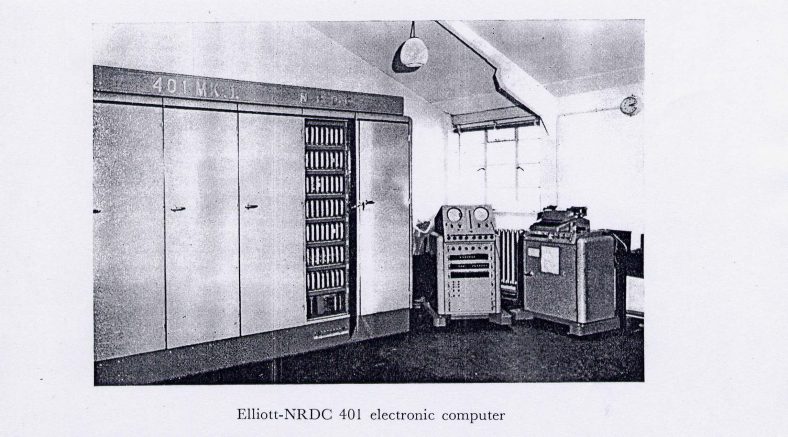

Elliott 401 Computer in 1954. Part of the processor units, the monitor, tape-reader and type-writer (on top). Credit: Rothamsted Archives

Harpenden was the home of the first electronic computer used in civilian research. Dr Frank Yates, head of the Statistics Department at Rothamsted, had built up a strong team of statisticians and computing assistants serving not only Rothamsted but also the agricultural institutes throughout Britain, and the experimental farms of the Ministry of Agriculture.

Computer hut by Rivers Lodge. Credit: Gavin Ross, 2016

By 1953 there was urgent need for greater computing power to cope with demand, and negotiations started to acquire the Elliott 401, the prototype computer built by Elliott Brothers and no longer in use. Finance was provided by the National Research and Development Corporation, NRDC, and a temporary hut was built alongside Rivers Lodge to house the machine and provide extra office space.

During ten years of service pioneering programs were written for the analysis of experiments and surveys, for model fitting, cluster analysis and crystallography. With very small capacity there had to be separate programs for each analysis, but the need for more general programs and standardisation of input conventions led to the development of early higher-level programming languages. This enabled the department to exploit the capabilities of larger and faster successor machines to produce general programs. Meanwhile the department greatly increased the number of experiments it was able to analyse, including many from research institutes in developing countries.

+, -, x, but no division

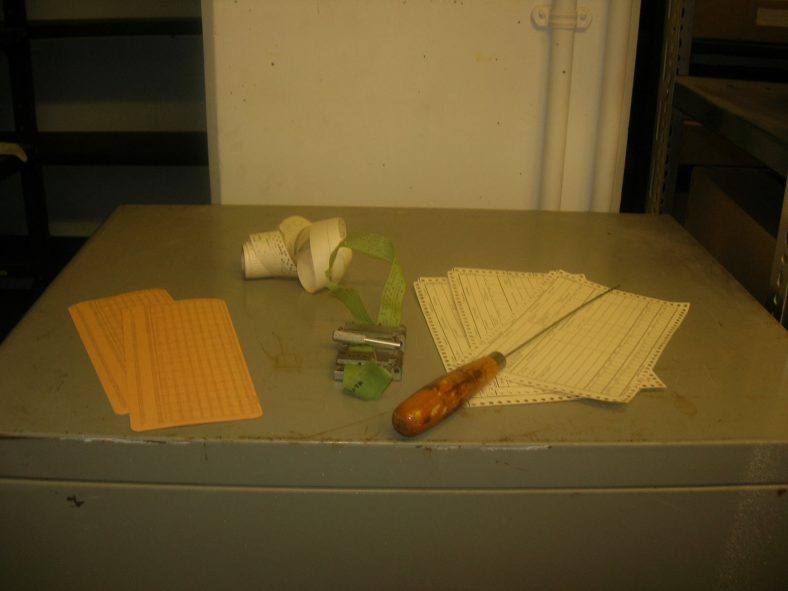

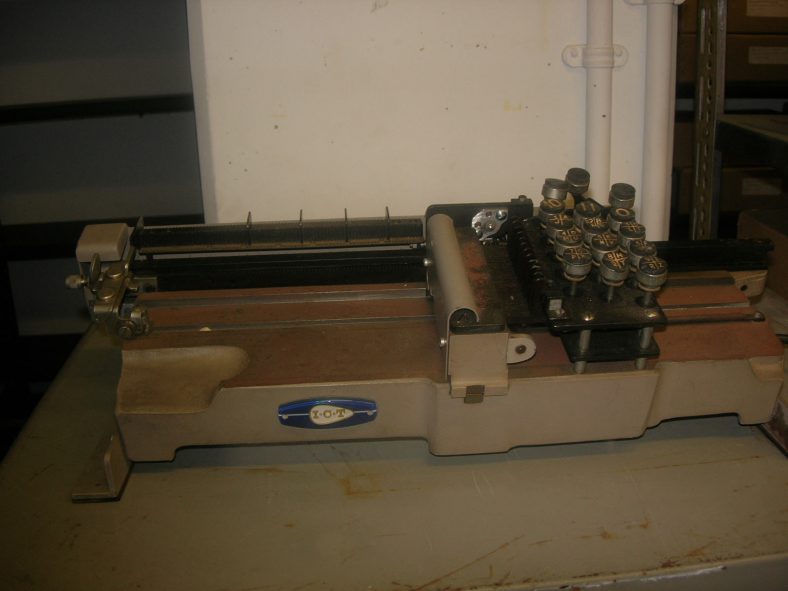

The Elliott 401 was developed from wartime radar technology, using electronic valves, occupying a large space and consuming considerable energy with very small capacity or speed by modern standards. Programs and data were originally stored on a magnetic disc, later replaced by a magnetic drum with capacity for about 3000 words of length 32 bits. There were only five ‘immediate access’ stores as the information on the drum could only be read as it rotated past the reading heads about 70 times per second. Input was from five-track punched paper tape, and output was initially to a typewriter, but later to punched tape which could be fed separately to be printed on teleprinters. A punched card reader was attached that could read about 15 cards per minute from less than half the columns on the cards. The inbuilt functions of the machine were very limited, allowing addition and subtraction and multiplication, but not division, and a few logical instructions and means of referring to different parts of the store. The first task for the department was to write basic programs for division and square roots and other mathematical functions, for sorting lists, manipulating data arrays, and handling tables and matrices. There were no facilities for text, apart from copying headings, and so program results were mainly set out as numbers only, which required annotation by hand before sending off to the user.

By the early 1960s faster computers were available, and a Ferranti Orion computer was ordered, with a new building to house it adjoining the hut. The Elliott 401 was finally shut down in July 1965 and handed over to the Science Museum, where it stands in a warehouse awaiting restoration by members of the Computer Conservation Society.

References:

Annual Reports of Rothamsted Experimental Station, 1954-65.

Lavington, Simon (2011). Moving Targets. Elliott Automation at the dawn of the computer age. Springer.

Punched cards and tapes. Credit: Gavin Ross, 2002

Manual card punch. Credit: Gavin Ross, 2002

Comments about this page

” The Elliott 401 was [..] handed over to the Science Museum, where it stands in a warehouse awaiting restoration [..] “

Not anymore ! As per 2017, it now sits at the Mathematics gallery of the Science Museum. Although not in working condition it is nevertheless very well preserved.

Add a comment about this page