Logo of the Chinese Industrial Co-operatives

What motivated George Hogg ** in China was a strong belief in the co-operative movement and what it could do to help the country’s development. He first heard of proposals to establish industrial co-operatives in China in the summer of 1938. China’s situation had become desperate: the advancing Japanese armies had destroyed its coastal industries, crippling the economy, and forcing the Nationalists to retreat to the largely undeveloped hinterland provinces. What was being proposed was to create a chain of small industrial units across unoccupied China, an army of economic resistance to help sustain the military effort against the Japanese invasion. The Chinese Industrial Co-operatives (CIC) would employ refugees to produce basic materials to meet the needs of war, operating at the frontlines and at the rear in both Nationalist- and Communist-controlled areas.

The origins of Gung Ho

Behind the idea was a group of progressive Westerners and Chinese, most notably the New Zealander and Shanghai factory inspector, Rewi Alley.

Rewi Alley

With China in a ferment of ideas about the need for social change and economic renewal to meet the national challenge, CIC’s vision of the country’s transformation through a mass-based participatory rural industrialisation gained initial support across a wide political spectrum. The Gung Ho – “work together” – movement, as CIC was also known, in many ways captured the spirit of the United Front to rebuild the nation through war, and the idea of village co-operatives, involving rather than marginalising the rural majority, combining self-help with mutual aid, spread quickly among political, business, diplomatic and Christian missionary circles.

Support flowed in from the US, Britain, especially the co-operative movement, and the overseas Chinese communities in South East Asia in the form of funds, materials and machinery as well as volunteers such as Hogg. CIC’s aim to give Chinese refugees from war the skills to rebuild their own lives had a strong humanitarian appeal. At the same time, China’s anti-Japanese resistance was seen as opening a new frontline in the fight against fascism.

George Hogg, c.1944

CIC was officially set up in August 1938. Hogg took up the post of publicity officer for the North West region at the end of October 1939. He was based in Baoji, a city 140 miles to the west of Xian, where the first CIC co-operative had been set up some months before. As the terminal for the railway from the East, the city had been in a chaotic condition, its streets overflowing with refugees: there were no refugee camps and few supplies. By the time Hogg arrived, Baoji was being transformed by CIC into ‘a co-operative city’ producing shoes, foodstuffs, blankets, towels, medical equipment and much else besides.

George Hogg – Headmaster of Shuangshipu Bailie School

Hogg soon became a CIC inspector, travelling in difficult and sometimes dangerous circumstances throughout the North West to investigate the progress and problems of village co-operatives. In 1942, he was appointed headmaster of the CIC Bailie School in Shuangshipu. By this time, he had begun to lose confidence in CIC. Amidst mounting frictions within the United Front, Alley had been dismissed from his post for ‘dealings with Communists’. CIC was falling under the influence of the right wing of KMT which sought more direct government control over the organisation, undermining its goals of decentralised development of worker-owned and managed enterprises, and its bipartisan stance.

Entrance to Shandan Bailie School, established in an abandoned monastery in 1944-45

Hogg and Alley turned to focus their efforts on the Bailie schools, so-named after with the Irish-American missionary, Joseph Bailie, who had been the first to introduce technical training into China.

Part of Shandan Bailie School, c.1947

Alley adopted the Bailie ‘hand and brain’ method of part-study-part-work as best suited to the CIC schools, which aimed to train skilled workers and future leaders for the co-operatives. CIC was to establish seven such schools, recruiting students from poor village families, war orphans and refugee children, and apprentices from the co-operatives.

The memorial erected in Shandan to George Hogg in 1984

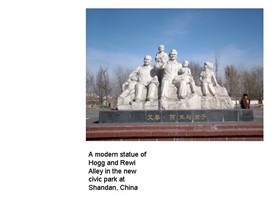

CIC continued to operate after the war ended in 1945, but following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 its work was wound up. During the Cultural Revolution, CIC came under criticism. However, Alley was able to revive the organisation in the early 1980s. The Shandan Bailie School was re-opened in 1984, and George Hogg’s grave restored. He himself was acclaimed by Deng Xiaoping as a ‘great international fighter’.

A remarkable endeavour

Hogg’s contribution is to be considered alongside that of Gung Ho, itself a matter of some controversy. The movement’s potential was vastly hyped up by sections of the Western media, something which angered Hogg, whose own much more pragmatic view of CIC’s achievements was based on grassroots experience. Alley’s original plan for 30,000 co-operatives had been far too ambitious: at best, less than 3,000 co-operatives were established with around 30,000 workers. Nevertheless, this is to be regarded as a remarkable endeavour in the worst possible circumstances of war, poverty, corruption, political persecution as well as inexperience.

CIC co-operatives generated tens of thousands of additional jobs for the rural populations, providing material assistance for the war effort. The CIC Bailie Schools trained technicians and managers who were later to make important contributions to China’s subsequent industrial development. The support from overseas not only helped to boost the morale of China’s resistance but also challenged negative Western stereotypes of China as the ‘sick man of Asia’. Hogg’s book, I See a New China, published in 1944 to acclaim from both sides of the Atlantic, in which he recorded his experiences as CIC inspector, provides an instance of this. In contrast with the usual ‘blood and guts’ style of war reportage, as well as the idealised Western media accounts of Gung Ho, Hogg’s down-to-earth account attests to his ability to engage with the ordinary rural Chinese, capturing in descriptions of their everyday life a resilience in adversity. The work stands today as a valuable and distinctive record of China at war.

* Dr Jenny Clegg, former Senior lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire, was co-author of a chapter on the Gung Ho movement in The Hidden Alternative: Co-operative values past, present and future, published by Manchester University Press, 2011. She spoke on George Hogg and the CICs at St George’s School, Harpenden on 12 October 2012 at an event organised by the Co-operative Group Members Area Committee in conjunction with the school. She continues to research and write about co-operatives in China, past and present.

** Ocean Devil: The Life and Legend of George Hogg by James MacManus, published by Harper Perennial in 2008, describes the formative influences on George Hogg.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page